Belarusian diaspora in Germany: past and present

Up to 50 thousand people of Belarusian descent live in Germany today. A notable Belarusian diaspora has been present in the country since the early 20th century

As of the end of 2022, official statistics indicate that 28,835 Belarusian citizens resided in Germany, comprising 19,300 women and 9,535 men.

Additionally, from 2000 to 2022, 8,133 Belarusians (5,432 women and 2,701 men) acquired German citizenship. According to German legislation, individuals naturalising had to renounce their Belarusian citizenship.

To this figure, we can perhaps add another one or two thousand individuals who received German citizenship in the 1990s, along with children born to naturalised German citizens of Belarusian origin, and migrants from previous times and their descendants. Thus, the total number of people of Belarusian descent in Germany can be roughly estimated at 45,000 to 50,000.

Noteworthy Belarusians living in Germany include Nobel laureate Śviatłana Aleksijevič, writer Alhierd Bacharevič, singer Vieranika Kruhłova (“KRIWI”), director Alaksiej Pałujan, singer Śvieta Bień (“Serebryanaya svadba”), and former Lukashenka propagandist Inha Chruščova, who supported the protests in 2020. The family of the disappeared oppositionist Jury Zacharanka resides here, and so does the opposition politician and high-ranked military officer Uładzimir Baradač. The famous writer Vasil Bykaŭ spent part of his exile in the 1990s and 2000s in Germany, scientist Barys Kit spent the last years of his life here, and Aleh Ałkajeŭ, a witness to the murders of Belarusian opposition politicians in 1999 and 2000, lived and died in Germany.

Historical context: from the Saxons on the throne of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania to Radio Liberty in Munich

Germany has a deep historical connection with Belarus. Augustus II the Strong and Augustus III the Saxon, father and son from the Saxon royal house of Wettin, served as Grand Dukes of Lithuania and Kings of Poland (and thereby also rulers of Belarusian lands) for a large part of the 18th century. Most Belarusian Jews, whose numerous community constituted up to a million people by the early 20th century, originated from Germany, migrating in the Middle Ages to Belarus due to persecution. Thanks to Yiddish, a language derived from medieval High German, and to Polish mediation, numerous German words are present in the Belarusian language.

Since the Middle Age, a noticeable German diaspora has existed in Belarus. Belarus briefly even shared a border with Germany, according to the formally declared borders of the Belarusian Democratic Republic of 1918 and after the annexation of West Belarus by the USSR in 1939-1941.

In the 20th century, Belarus witnessed two wars between Germany and Russia (or the USSR) and was twice under German occupation. The first, comparably mild occupation occurred during the First World War. During this occupation, Belarusian language gained an official status in Belarus for the first time since several centuries. The second, much harsher occupation of Belarus by the German Nazis, took place in 1941-1944 and was accompanied by massive Nazi terror against Belarusian civilians, including a genocide of the Belarusian Jewish population. As a result of the Second World War, post-war Soviet repressive policies and Russification, and the wave of Jewish emigration in the 1970s and 1990s, the community of Yiddish-speaking Belarusian Jews and the diaspora of Belarusian Germans virtually ceased to exist.

Belarusians in Germany in the early 20th century and after World War 2

At the beginning of the 1920s, the diplomatic mission of the newly independent Belarusian Democratic Republic and the Belarusian Press Office, affiliated with it, operated in Berlin. Weimar Germany recognised the passports of the Belarusian Democratic Republic. Later, Germany formally established diplomatic relations with the totalitarian Soviet puppet state, the Belarusian Soviet Socialist Republic.

In any case, when independent Belarus established diplomatic relations with Germany in the early 1990s, Belarusian diplomats used the term “restoration” of diplomatic relations rather than “new establishment”.

During World War II, several Belarusian organisations and pro-German propaganda publications existed in Germany, primarily in Berlin, under the control of the Hitler regime. The Nazis sought to exploit the Belarusian pro-independence movement to strengthen their occupation power in Belarus, while certain Belarusian politicians sought to use the Nazis to gain Belarusian independence or at least to create non-Soviet Belarusian institutions and armed forces.

Simultaneously, many thousands of Belarusian Ostarbeiter forced workers were taken to Germany by the Nazis. Modern media estimate it at 380,000 people.

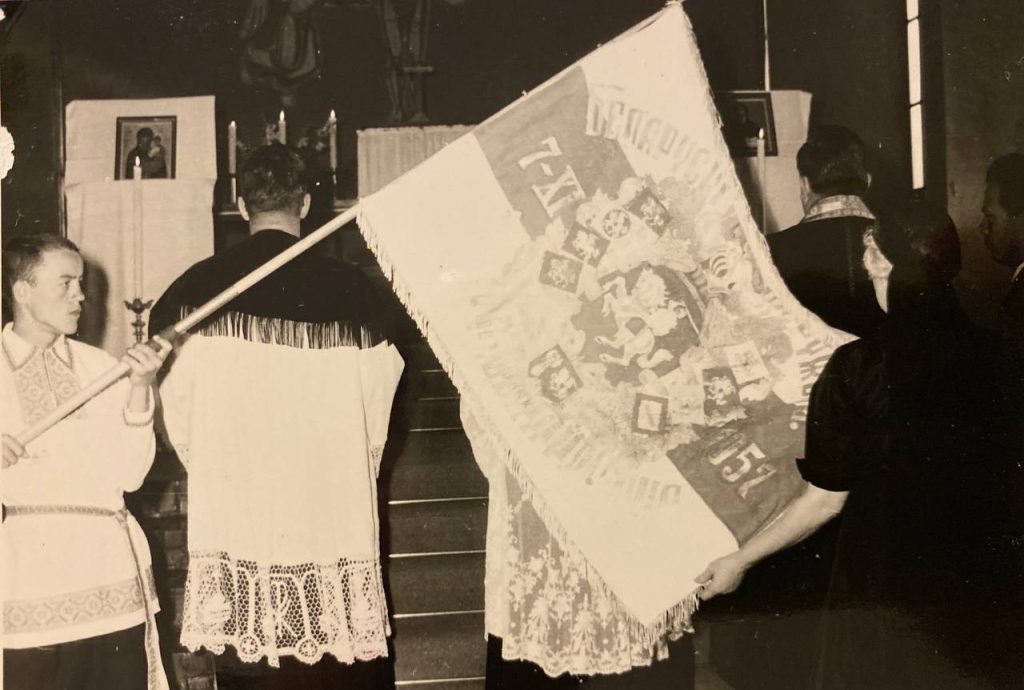

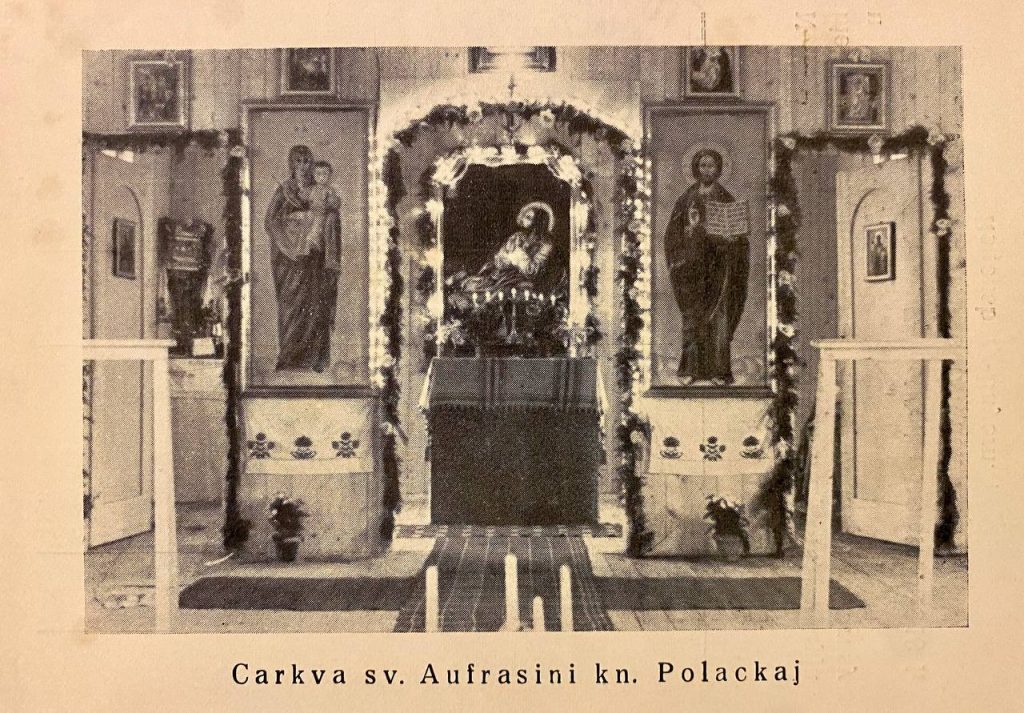

After the war, tens or even hundreds of thousands of Belarusians passed through West Germany and the UNRRA refugee camps located there. These were people who escaped from Belarus, where the Soviet Stalinist regime was re-established to replace the Nazi occupation, and Belarusian Ostarbeiter, of whom at least 150 thousand avoided forced return to the USSR, where many of them could face repressions from the communists. In the archive of the Francis Skaryna Library in London, there are photographs of wooden temporary Belarusian churches in Regensburg and Rosenheim, scout certificates, collections of newspapers and documents of Belarusian communities in Germany.

Photos of Belarusians in Germany in the 1940s – 1970s from the collection of the Francis Skaryna Library in London

None of this, no organisation or newspaper, has survived since then. For most Belarusian refugees after the Second World War, Germany was a transit point from where they moved on – to Britain, the USA, Canada, or Australia. In the UK and North America, the associations created by them are still active.

A peculiar Belarusian community in West Germany during the Cold War was probably the Munich-based Belarusian editorial office of Radio Liberty (today, Radio Free Europe / Radio Liberty). During the Cold War, it was one of the key centres of the Belarusian anti-Soviet informational resistance. In 1995, RFE/RL moved to Prague, where it is still located today, which ended the organised Belarusian presence in Germany.

There was no organic generational change of the Belarusian diaspora in Germany and no transfer of institutional heritage, as happened in Great Britain, the USA, or Canada. Neither was there much support from the diaspora for the newly established Belarusian embassy in the early 1990s – except for a brief cooperation with Radio Liberty. Unlike this, for example, in New York, local Belarusians handed over the first white-red-white flag for the representation of Belarus at the UN in 1991, and in London, they even provided the Belarusian embassy with its first premises.

Only a few monuments and artifacts remained in Germany – the famous monument to the heroes of the Sluck Uprising in Mittenwald, Bavaria, the amateur museum and archive of Jury Popka in Leimen, which he bequeathed to the independent Belarusian state. Many graves of Belarusian activists buried in Germany after the war were neglected and have already disappeared.

Post-Soviet times: a numerous but unorganised diaspora

Photos of Belarusians in Germany in the 2000s from the personal archive of Alexander Moisseenko

After Belarus regained independence, a wave of Belarusian labour migrants and political refugees came to Germany. However, economic migration was smaller than that from neighbouring post-communist countries, and political exiles mainly settled in Warsaw, Vilnius, and Prague rather than in Germany.

The post-Soviet Belarusian diaspora in Germany lacked organised structures, with separate small communities and informal gatherings in Berlin.

In 2001 and 2004 Belarusian politicians, former activists of the Belarusian People’s Front, made at least two attempts to establish organisations in Germany, but there is no available information about their current activities.

After 2020

The year 2020 marked significant changes in the Belarusian diaspora worldwide, and Germany these changes were probably stronger than elsewhere. Mass protests against the falsification of presidential elections and political repression in Belarus led to the formation of RAZAM e.V., an all-German association of Belarusians. As of the end of 2023, RAZAM had approximately 270 members across the country.

Belarusian pro-democracy protests in 2020-2021, photos are courtesy of RAZAM e.V.

Since then, RAZAM has been organising cultural events, communicating with German politicians, and participating in charitable activities. The Belarusian diaspora in Germany, unified by RAZAM, has been providing support to hundreds of Belarusian political refugees. The organisation collaborates with Mara e.V., another Belarusian-founded NGO in Germany, in assisting political refugees.

Cultural events organised by RAZAM, such as the Minsk x Minga festival in Munich, Belarusian studies courses at Ludwig and Maximilian University in Munich, or poetry readings in North Rhine-Westphalia, have become significant contributions to popularising Belarus in the German society.

Belarusian artistic and cultural events regularly take place in Berlin’s Haus der Statistik. Regular cultural and information events, days of Belarusian culture, take place in Bremen, where there is also a Solidarity Committee with the participation of local politicians, journalists, and cultural figures. In southwestern Germany, the cultural association Kulturverein Belarus, created by Belarusians.

In Bavaria, the Münchenščyna festival takes place every year with cultural workshops for the whole family. There are Belarusian language courses for children in Munich and Berlin. Meetings of local Belarusians take place in Bremen and other cities. On important dates, Belarusians visit the monument to the heroes of the Słuck Uprising in Mittenwald.

In March 2023, RAZAM received the Gustav Heinemann Civil Award for its human rights and civic activism. It has become the first Belarusian diaspora organisation mentioned in a Bundestag resolution.

Another important organisation is the German-Belarusian Society (deutsch-belarussische gesellschaft, dbg), which for a long time was mostly an association of Germans interested in Belarus but recently became more open to participants from the Belarusian diaspora in Germany. The annual Minsk Forum held by the dbg – now temporarily held outside of Minsk – became a platform for the meeting of members of the Belarusian civil society and Belarusian democratic politicians from different political parties.

Germany will always be a place where many Belarusians live. There are many objects of Belarusian cultural heritage and works of art created by Belarusians in German museums. In different parts of the country, you can find many architectural monuments related to Belarus and Belarusians, and even Belarus-related cultural festivals, such as the Landshut Wedding, one of the largest festivals of medieval culture in Germany, dedicated to the memory of the wedding of the Bavarian prince George and the Polish-Lithuanian-Belarusian princess Hedwig Jagiellonica.

Germany, as the largest country in the European Union, plays a crucial role for Belarus. The Belarusian diaspora can significantly contribute to Belarusian-German contacts.

By Aleś Čajčyc

Member of the Board at the German-Belarusian Society

The original Belarusian version of the article was prepared for Zapisy BINiM, a Belarusian-American academic publication

Useful links:

https://razam.de/ – RAZAM e.V.

https://www.facebook.com/minskminga – Minsk x Minga, the annual festival of Belarusian culture in Munich

https://www.dbg-online.org/ – German-Belarusian Society (dbg e.V.)

https://t.me/+7e1qhdQqQxphYTE6 – Belarusian Heritage in Germany, community in Telegram

https://www.kub-verein.de/ – Kulturverein Belarus

https://maraverein.de/ – Mara e.V.

* Data source: destatis.de